The question my ADHD diagnosis didn't ask

Thoughts on medication, alternative interventions and moral considerations

Welcome to the third essay in this series. ADHD and medication is a contentious topic, so it’s not surprising many of you asked me to write about it next. As a neuroscientist studying ADHD and diagnosed myself, I have some thoughts – they’re still evolving, but this is my attempt at articulating them. P.S. my work was featured in Science News!

When I was diagnosed with ADHD, I was told one of the most effective treatments was medication, and I was offered a prescription right there on the spot. I distinctly remember the immediate resistance I felt in my body.

Of course, I knew from my academic research that pharmacological treatment is indicated as a first-line option for ADHD, and I have friends who’ve expressed how grateful they are for their ADHD medication. But, somehow, it felt wrong when it happened to me.

Looking back, I understand my resistance better now. I was never asked how impairing my symptoms actually were considering my current circumstances (job, relationships etc) and what coping mechanisms I’d already developed. The focus was purely on symptom checklist → medication.

In the UK, where I live, prescriptions for ADHD have risen 18% year on year since the pandemic, while in the US dispensing of stimulants for ADHD increased by 60% over the past ten years or so. Which begs the question: is medication really the best option? And what are the risks and moral considerations?

First, let’s have a look at how we got there.

A little history of ADHD interventions

I’m deliberately using the word interventions and not treatments here, because many of these don’t actually “treat” ADHD – they partially alleviate or mask certain symptoms. And, as I’ll touch on later, medication is not the only way to support people with ADHD. So, here’s a quick timeline:

1937: Dr. Charles Bradley first reported that Benzedrine (racemic amphetamine originally marketed in the 1930s as a decongestant inhaler) improved behavior and school performance in children with behavioral issues. This is the earliest record of stimulants being used for what we now call ADHD.

1950s–1960s: Methylphenidate (Ritalin) was introduced in the 1950s and became widely used in the 1960s for “hyperkinetic reaction of childhood,” the precursor term for ADHD. Diagnostic criteria were still vague, focused mainly on hyperactivity.

1970s–1980s: Diagnostic definitions shifted. DSM-III introduced ADD with or without hyperactivity, and DSM-III-R renamed it ADHD. Stimulant use broadened but was debated.

1990s: ADHD subtypes (inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive, combined) were formalized in DSM-IV. Extended-release stimulant formulations were developed to improve adherence and reduce stigma of taking multiple daily doses. First major non-stimulant explored. Concerns about overdiagnosis and misuse surfaced.

2000s: Atomoxetine (Strattera) approved as the first non-stimulant specifically for ADHD, and Guanfacine XR (Intuniv) and Clonidine XR (Kapvay) approved for pediatric ADHD. Debate intensified about rising diagnoses.

2010s: Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) gained popularity, marketed as longer-lasting and with lower misuse potential. Recognition of adult ADHD increased and treatment expanded beyond children.

2020s: ADHD diagnoses and prescribing rose sharply during and after the pandemic, linked to the expansion of telemedicine and increased recognition in adults. Viloxazine XR (Qelbree) approved in 2021 as a novel non-stimulant. Growing attention on shortages (e.g., Adderall) and concerns about misuse/diversion.

Although these days guidelines emphasize multimodal treatment (behavioral interventions + meds), stimulants remain first-line in many cases. Non-stimulants are options for people who don’t tolerate or respond to stimulants.

There are many issues with this meds-first approach. Some people experience side effects which include appetite suppression, insomnia, increased heart rate and blood pressure, and mood changes. Tolerance may develop and effectiveness can wane during the day, leading to a “crash” when the drug wears off. Misuse is a real concern, particularly among adolescents and young adults.

Long-term, the picture is even less clear. Safety questions remain about decades-long effects on brain development and cardiovascular health. And there are of course moral and ethical concerns as reliance on medication may obscure systemic contributors such as school and work environments, and frame ADHD primarily as a pathology.

Perhaps fortunately, that’s not the entire picture.

What the timeline misses

People with ADHD didn’t passively wait for medical interventions to arrive. Just like with any other condition, people with ADHD will seek ways to cope. And most of the time, they’ll find one.

Forms of coping include stimulating substances like coffee and tobacco, exercise or physically demanding work to help channel their restless energy, creative and entrepreneurial pursuits that accommodate hypercuriosity and reward novelty-seeking, and structured rituals to self-impose a form of external order.

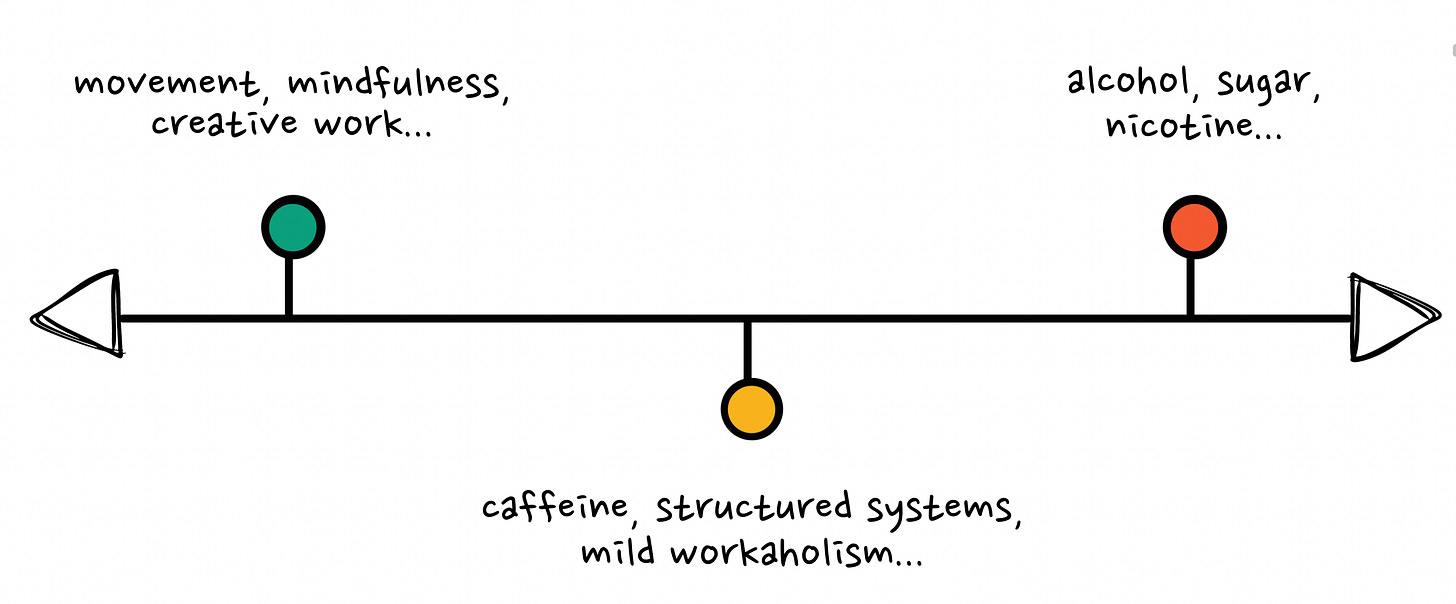

These strategies exist on a spectrum. Some are beneficial: regular exercise, creative outlets, careers that play to ADHD strengths. Some are in the middle and highly context-dependent: workaholic tendencies, relying on caffeine to stay focused, rigid scheduling systems.

And some are actively harmful: alcohol, nicotine, and any ways to cope that provide temporary dopamine hits at significant cost.1

For instance, I started smoking when I was 11. I loved how it helped me feel less restless and more focused. By 18, I was going through a pack a day. Throughout my twenties and into my thirties, I struggled with alcohol abuse, which calmed my racing mind.

This was textbook undiagnosed ADHD brain seeking dopamine regulation through whatever was available.

(I’m not alone in this pattern: research consistently shows that people with ADHD have significantly higher rates of substance use disorders, and many describe feeling “normal” for the first time when using certain substances, which isn’t coincidence as both ADHD and addiction involve dopaminergic dysregulation)

Whether it’s alcohol, prescribed amphetamines, or even exercise, anything that helps regulate executive function and mood carries the potential for dependency: you can absolutely become addicted to exercise, to work, to the rush of constant crisis.

The pattern is the same: you find something that makes your brain feel ‘right’, and you chase it.

Still, the problem isn’t that people with ADHD are seeking regulation – they are, inevitably. It’s whether we’re doing so consciously, safely, and with the appropriate kind of support.

And this is exactly what should be assessed during diagnosis. A clinician should be asking: What are you already using to cope? What’s working? What patterns of dependency exist?

But that’s not what happened to me.

What else works?

I’m not saying medication is intrinsically wrong. For some people, in some contexts, it genuinely is life-changing. My concern is that medication offered reflexively at diagnosis isn’t just inadequate, it might be actively harmful.

We suspect that ADHD traits likely evolved in environments vastly different from modern life, and the “disorder” might emerge from the mismatch between our neurology and today’s demands: sedentary work, arbitrary deadlines, sedentary work, constant digital stimulation.

Shouldn’t we be assessing whether the environment is the problem and lifestyle changes might help before medicating the person?

Researchers (including in my lab) have been exploring other interventions: exercise (we know physical activity has positive effects on attention and executive function), mindfulness practices (like meditation), dietary approaches (including omega-3 fatty acid supplementation), digital therapeutics (such as video game cognitive training programs), neurofeedback…

This is what bothers me most about my diagnostic experience: none of these were mentioned. Not as alternatives, not as complements to medication, not even as questions about what I was already doing.

I decided to turn down medication. Instead, I turned to movement and mindfulness – mostly ecstatic dance, meditation, and journaling. And I unwittingly built a career that rewards hypercuriosity, encourages nonlinear thinking, and gives me tons of autonomy over how I manage my time and energy. I’m not a fan of the word ‘superpowers’ but it’s undeniable that in this context many of my ADHD traits have actually become pretty useful.

I recognize this path required privileges many people don’t have: education, savings from my first job at Google, risk tolerance, and work in fields that value my particular cognitive style.

For someone without the option to restructure their environment (and I recognize that’s most people given current economic realities) the situation is more complex. But that doesn’t mean medication should be automatic; it means we need better questions about what environmental changes are possible, even small ones.

I do remain open to medication if ADHD becomes unmanageable through other means in the future. However, I suspect that with the right environmental fit and support systems, only a small subset of people with ADHD truly require pharmacological intervention – though that’s unfortunately not the world we live in yet.

Now, the uncomfortable question this raises is: how many people are being medicated to function in environments fundamentally incompatible with their neurobiology, when restructuring those environments might address the root cause?

Sure, not everyone can become self-employed or redesign their career. But asking the question challenges our reflexive reach for the prescription pad.

TLDR: ADHD interventions should assess the whole person in their full context – their current coping strategies, their environment, their ambitions, their resources – not just check symptom boxes and prescribe medication. Until we do that, we’re just trying to fix the person rather than addressing the mismatch.

As usual, I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments!

For what it’s worth, I do believe alcohol and tobacco can play meaningful roles when used ceremonially rather than consumed the way we tend to in modern society, but that’s a different conversation about our relationship with these substances more broadly.

This is such a a wonderful exploration of your lived experience and current research (and past!). Thank you for writing and sharing it.

Loved this. Your point about clinicians never asking "what are you already using to cope?" before reaching for the prescription pad – that's the gap I see constantly. You're naming the real tension: ADHD shows up as a mismatch as much as a "deficit", and meds can either buy breathing space to fix the context… or prop up a bad one.

What tends to work best in my experience as a doctor (and patient) working in ADHD is a both/and plan framed as a time-boxed experiment, not a forever decision. A simple scaffold I use:

CARE — Context, Aims, Risks, Experiments

Context. Map the current coping stack (caffeine, overwork, crisis-deadlines, exercise) plus friction points at work/home. Name one environment change you can make this week: written agendas, 3-box task list (Must/Should/If time), 10-minute walk after lunch, phone charging in another room after 9pm.

Aims. Pick 3 outcomes that matter in real life – reply to emails within 24h, start tasks within 2 minutes, lights-out by 11pm. Baseline them for a week.

Risks. Sleep, appetite, pulse/BP, mood rebound, anxiety spikes, dependency patterns (including "productive" ones like workaholism). Decide upfront what would make you stop or dial down.

Experiments. Stack one change at a time. If medication is used, treat it as a scaffold: lowest effective dose, daytime cut-off, weekly check-ins, one "med-light" day to test whether skills generalise. Review at week 6 and week 12 with the original aims in hand.

Medication isn't a moral failure. Nor is declining it. The red line I try to hold: never widen the mismatch (longer hours, impossible workloads) just because the brain feels smoother today.

I'd be curious to know, if you had 12 weeks and three metrics, which ones would you choose to track?